They come at dawn

I’m ashamed to say that I work for a university whose President recently decided to invite police onto campus to violently remove a small, peaceful pro-Palestine encampment less than 48 hours after it was first erected. Dressed in riot gear, wielding batons, gas canisters, and pepper bullets, the cops arrived at 4.45am just as the first light of dawn was appearing, and the small group of camping demonstrators were mostly asleep.

Sign at the University of Alberta Palestine encampment reading “Welcome to the People’s University for Palestine ‘for the public good’” [a university motto]. May 10 2024.

Later that same day, long after our quad had been cleared of bent tent poles and strewn books, a large crowd of demonstrators walked from the legislature in Edmonton, across the North Saskatchewan river, and onto the University of Alberta campus. After the march organizers had a little back-and-forth with various security agents, we streamed onto the quad, chanting, listened to speakers describe the morning’s events, held up our signs, talked, sat on the grass. That protest lasted several hours, and then everyone went home—vowing nonetheless to return another day. The university leadership made much of their own generosity in allowing it to happen, signalling that peaceful protest and free expression were indeed within our rights. But encampments were not.

Marching for Palestine and to protest the encampment sweep. May 11 2024.

I’m curious about this distinction. What’s is it about an encampment that merits police violence that doesn’t apply to a demonstration? Not many of the answers I’ve heard draw this line: they make arguments that could equally apply to any demonstration at any time.

Perhaps the biggest difference is that an encampment involves sleeping and physical structures that remain in place overnight. It might become “entrenched”! A demonstration comes and goes, leaving only trampled grass and placards protruding from garbage cans. It is transient, a creature of the daylight.

So, what is so bad about shelters, sleeping, and the night? Sleeping protestors in flimsy tents are at their most vulnerable, and the small hours is when they are least likely to be inciting others, drawing a crowd, or picking fights. Perhaps a University President could respond that sleeping people cannot be expressing political opinions. They are not engaged in the activity that freedom of expression protects. But police don’t (at least as a matter of principle) pick off protestors from marches if they dally, stop chanting, or become distracted by a conversation with a friend. Being continuously and actively expressive through voice and movement has never been required as a condition of that Charter right.

The police came—as police do—at dawn. “Dawn raids” have a history: they have the element of surprise, pulling alleged drug-dealers or weapons-runners or mafia bosses from their sleepy beds, where they are most easily found and least likely to resist. But nocturnal attacks are also used against vulnerable people at their most vulnerable: as in the infamous New Zealand racist police campaigns against Pacific Islander overstayers, or cases like Breonna Taylor, who was woken from sleep and shot dead by armed police storming her apartment in search of her boyfriend.

Houseless people are completely familiar with this strategy of securitization. Being “moved along” is a feature of street life, and in many cities, police routinely tear down tents or temporary shelters used by houseless people. Being “transient” is thus both cause and effect. Hostile public architecture—things like bench dividers, spikes, angled seats, and sprinklers—inhibits everyone from sleeping in public, but targets and disproportionately affects houseless people. Public space becomes space to move through rather than gather in, and is rewritten as private property on which encampments are trespassing. Houseless people in Edmonton who are moved along are disproportionately Indigenous, being violently displaced within their own land. The students recognized these connections from the beginning. The University—more powerful, more brazen, and much less sophisticated—simply claimed Treaty 6 territory as its private property, along with the right to evict people protesting settler colonialism (here and in Gaza). As Indigenous scholars acerbically observed, the University’s statements on trespass appeared on webpages that standardly include a territorial acknowledgment in the footer.

A lot of this has to do with optics. A camp of bright blue and orange tarpaulin stands out. Whether it is out of place for the bourgeois neighbourhood, or incongruous against ivy-covered buildings on campus, it visually marks a departure from aesthetic norms. It draws attention, and references something that passers-by might not consider (or would rather not know). It makes for stark press photos (pro and con), and is eminently Instagrammable. By not moving on physically—by becoming dug in, solidly established—an encampment implies an intractable problem. For those wanting to draw attention to the genocide in Palestine, this is presumably one of the goals: this geopolitical conflict has been papered over, “moved on,” by a global desire to turn away from the horrors in Gaza. An encampment that is always there is difficult to ignore.

Clearing an encampment using police is also bad optics. Police almost always declare that there was no violence, no injuries, a judicious use of persuasion rather than an overt display of militarized force. And that is never true. That’s another reason they come at dawn. Better to do the dirty work at the time of day when the fewest witnesses are there or can be summoned, especially when youth (circadian night owls) are groggiest. It’s hard to video your own beating [TW: police violence].

Last winter in Edmonton the police tore down a large number of encampments for houseless people. Deemed a danger to public safety, “police showed media an array of weapons found at encampments, including swords, knives and guns.” The campers, we were told, were also a danger to themselves and each other: they have started fires or fights, people have died of overdoses. Meanwhile, houseless people die in startling numbers outside encampments, and use shared spaces for the purposes of mutual aid. (Many say that shelters are more dangerous.) It’s uncanny. The reason given for razing the pro-Palestine encampment? It was a danger, because it contained potential weapons (screwdriver, a mallet) and needles (an overdose kit, crafting supplies) (found after the raid, but used to justify it); there were pallets nearby that were flammable; “outside agitators” might be hidden in their midst, or arrive to pick a fight; the university could not guarantee the safety of the participants. They simply had to invite riot police to threaten, hit, and gas them. For their own safety and ours.

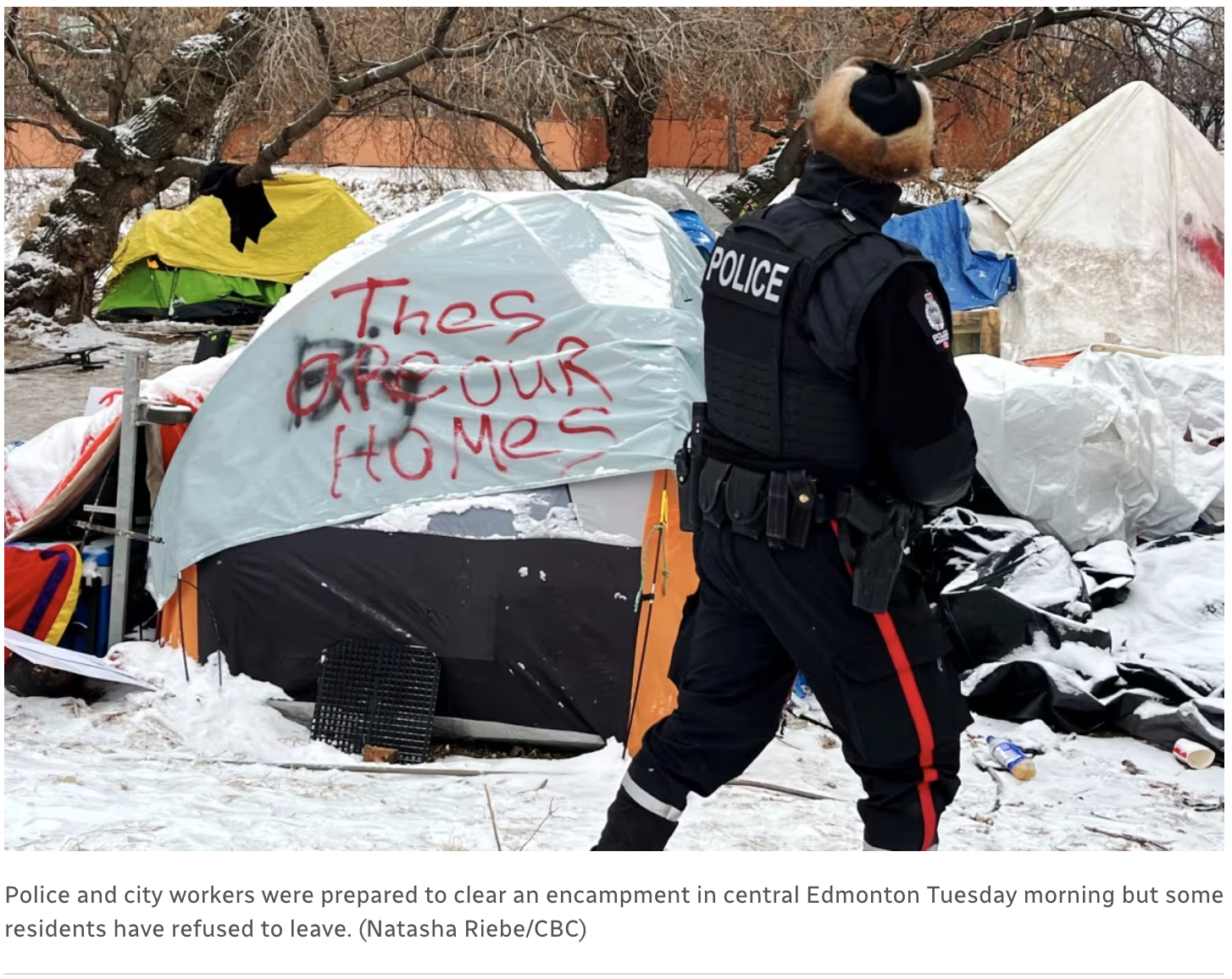

A police officer walks past a group of tents and tarpaulins in the snow. Written on one of the tents are the words, “Thes are our homes.”

Something else happens when an encampment is created. It becomes a community. Overnighting in a place implies you are living there—it’s a kind of domesticity and even intimacy that passing through doesn’t connote. (Not for nothing do exercises in ésprit de corps involve overnight retreats and spending a lot of time on shared projects with one’s comrades.) “These are our homes,” reads the spray paint on a houseless person’s tent. Although short-lived, the U of A encampment was homey and friendly, with students and faculty chatting, reading, studying, snacking. In fact, I was struck by how much more of a positive environment it was than the 1960s-era classrooms we teach in, which have toxic air, are dark and often cramped, with broken and uncomfortable furniture, and dysfunctional tech. The physical space of the neoliberal university, especially post-pandemic, is alienating and alienated. Why did we ever come back from Zoom, if it was only going to be like this? Tuition and fees are so high now that most of our students work long hours in retail and service industries. They are not much indulged with the experience of “campus community,” including journalism, athletics, reading groups, political causes, or the clubby experiences that boomers enjoyed. The opportunity to be with others—students and teachers—in a shared space of intensive learning and debate used to be the raison d’être of a university education. Now it is a disappearing and marginal luxury. Encampments have the potential to make something intellectually and political exciting and authentic, something explicitly opposed to the emphasis on technocratic, vocational, depoliticized, uncritical how-to learning that universities (falsely) imagine is the reductio of STEM education. Perhaps this also makes them generative—and threatening to technocrats—in ways that exceed their manifestoes.

In his provocative book, Law by Night, legal theorist Jonathan Goldberg-Hiller makes the argument that massed, sleeping bodies in public space can be understood to be exercising a right to be there. They may not be shouting slogans, but they can nonetheless claim to be occupying political space in the service of a cause. Perhaps they are exercising a right to disrupt business as usual. With their curfews, on-the-hoof policies about pre-approved actions, and other attempts to control time and space, university leaders willfully misunderstand how protest works. Nothing was ever won by being docile, compliant, private, constrained, ignorable. Putting a stop to genocide in Palestine, like genuine decolonization in Canada, will require actions that are visible, public, community-building, embarrassing, fearless, and truthful. We will have to become entrenched.